The early 20th century was a time of extensive research to better understand—and better control—the properties of flours used to produce quality breads. In 1920, Marcel Chopin contributed to this effort and filed a patent describing the Extensometer (French patent no. 525.986). The Extensometer simulates the expansion of a cell in dough, which it reproduces by expanding a previously prepared dough disk under precise conditions. The invention was supplemented in 1937 (French patent no. 925-017), when Marcel Chopin himself added an extractor kneader to his invention. The Alveograph was born!

What is an Alveograph anyway?

The Alveograph is an apparatus for measuring the properties of wheat flours based on the observation of the deformation of a dough bubble. An Alveograph is always comprised of two inseparable parts: the kneader and the Alveograph itself.

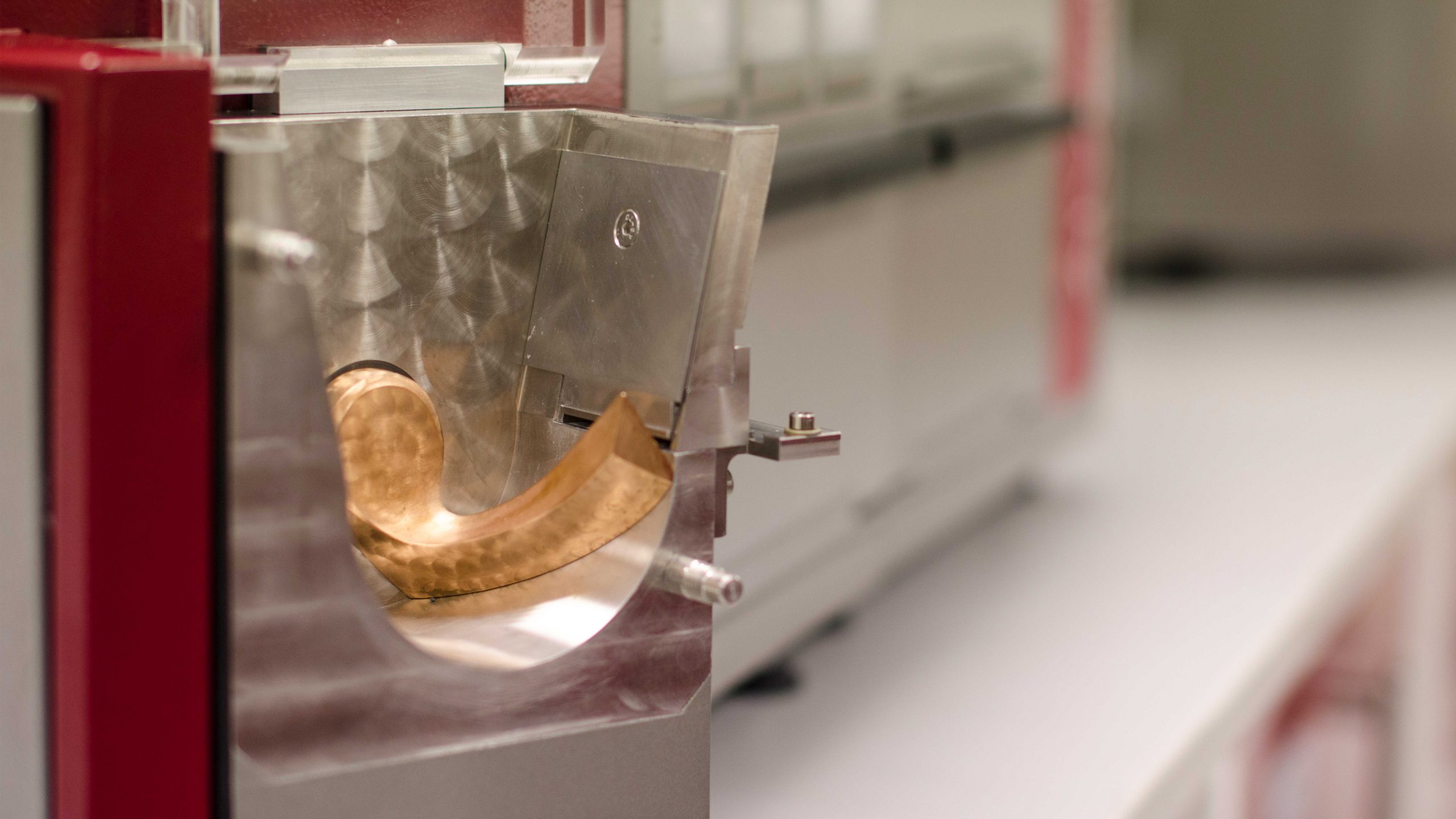

Despite being less spectacular and photogenic, the kneader-extractor is undoubtedly the most important part of the assembly. Successful kneading accounts for 80% of a successful test. Technically, the kneader is designed to perform optimal kneading of a 250 gram flour mixture with 50% added water (15% H2O base). This brings us to the constant hydration test. The sequence involves one minute of mechanical kneading followed by one minute of manual kneading and then an additional six minutes of mechanical kneading.

The minute of manual kneading is crucial because it ensures that all the flour undergoes hydration and kneading and that there are no remaining areas in the mixing bowl with unhydrated flour. At the end of this period, the direction of rotation of the mixer (the kneading element) is reversed in order to push the dough through a calibrated window used to determine the thickness of the piece of dough.

It is likely this part where Marcel Chopin’s inventive genius was the most strongly exhibited. By giving the mixer its particular curved shape, it is possible not only to push the dough out of the kneader in a straight line, but also to align the protein chains to form a homogeneous gluten network.

Many attempts have been made to work with doughs from other kneaders, but none have been able to achieve the levels of repeatability and reproducibility (see “Estimating a method’s accuracy”) achieved with the original kneader-extractor.

As they are extracted, five pieces of dough are cut, rolled, cut into disks, and placed in a resting chamber. This phase, which is carried out under specific temperature and humidity conditions, is also very important for the success of the test. It is during this period that the protein chains finish their structuring.

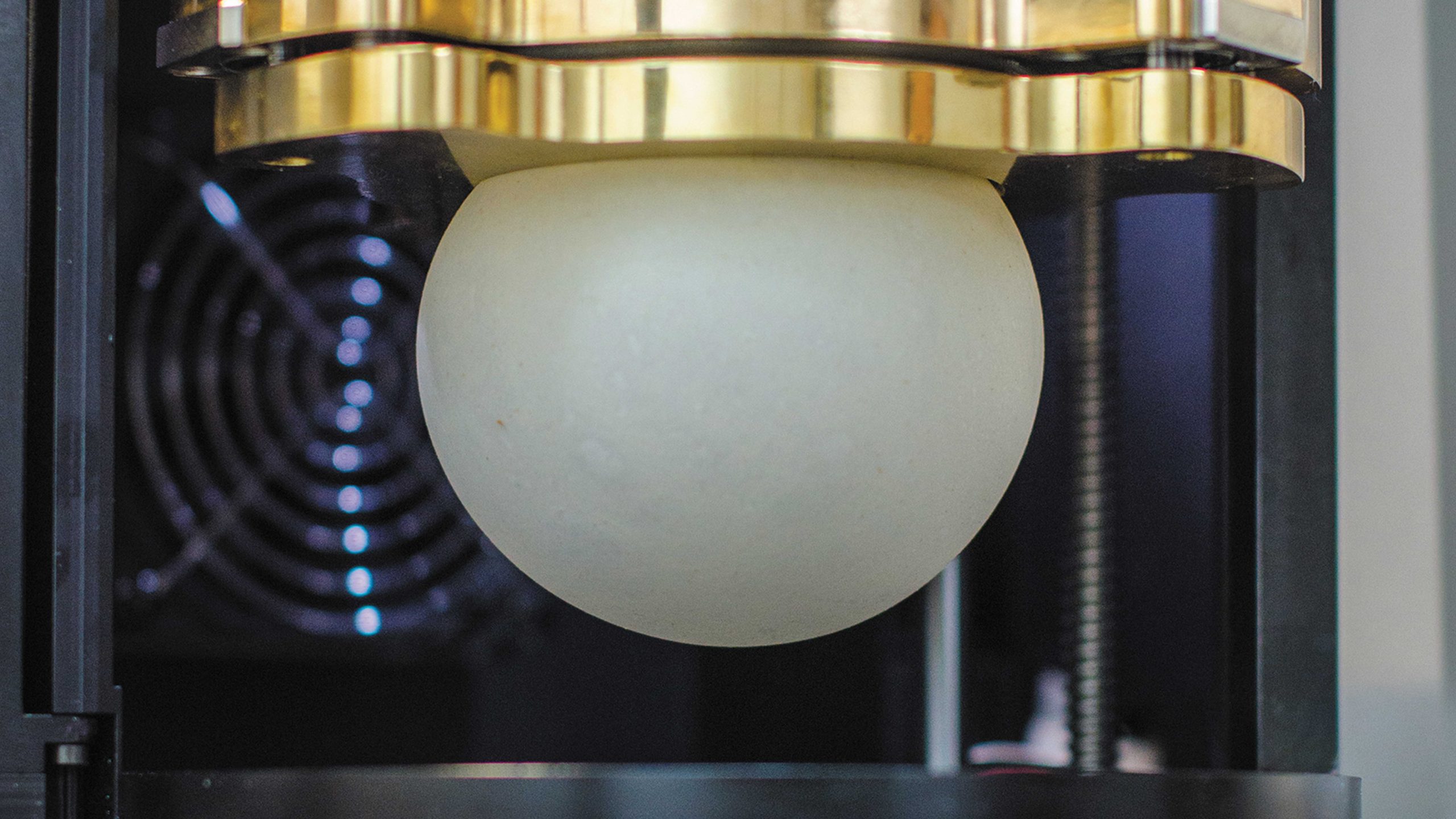

The next step consists of placing the piece of dough onto the Alveograph and pressing it at a set speed to give it a defined thickness. The piece of dough is then inflated with a calibrated flow of air while the system records the change in pressure inside the bubble over time, until the film of dough breaks. This operation is repeated on the five pieces of dough, and the five measurements are averaged to obtain the final result.

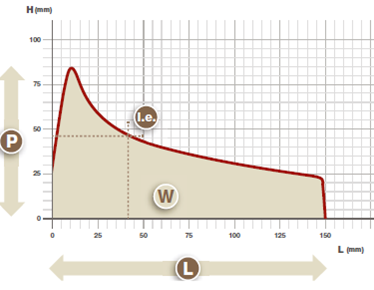

The Alveograph’s curve shows the pressure as a function of time. What the curve shows is closely comparable to what happens when we try to inflate a balloon.

At first, the piece of dough resists deformation. Because air is continuously added and the volume receiving this air is small, the internal pressure increases. The more the dough resists, the greater the pressure. On the curve, the maximum value “P” corresponds to the dough’s tenacity (resistance). To a baker, this is known as the dough’s “consistency.”

As with a balloon, once the resistance is exceeded (due to the addition of air), the piece of dough will start to form a bubble. In the case of dough, the bubble’s volume increases very rapidly, and its internal pressure drops, causing the curve to start descending. This will happen more quickly if the dough is not very elastic. The rate in decrease between the “P” value and the pressure value at a particular point on the curve is used to measure the “elasticity index.” This elasticity represents the dough’s capacity to retract after deformation, which explains why some pizza doughs have an unfortunate tendency to be the wrong size.

The bubble continues to deform until the dough film is so thin that it breaks, exactly like a balloon bursts if it is over-inflated. The time elapsed before reaching this breaking point is also expressed as a distance and represents the “G” or “L” both of which correspond to the dough’s extensibility. For bakers, this concept expresses the dough’s capacity to stretch.

Other parameters are also calculated, such as “W” for the total area under the curve, also known as the “baking strength.” We can also calculate the P/L ratio to compare tenacity versus extensibility.

All of these properties depend on the quality of the proteins (which have varying levels of tenacity, extensibility, and elasticity), the damaged starch, and the ash content (which increases tenacity), along with the various added ingredients.

Today, the Alveograph is an internationally recognized standard method (see “Standardization”). It is the preferred tool of millers, who use it to choose and mix their wheats, inspect and improve flours, and comply with specifications. It is also widely used in the secondary processing industry among ingredient suppliers, breeders, research institutes, and others.

Unlike some traditional ideas, the Alveograph is by no means limited to a particular type of wheat or flour. It is equally effective in processing hard and soft wheats (there is even a protocol for durum wheat) (see “Hardness”) and flours for cookies, crackers, all types of bread (baguettes, sandwich breads, and flatbreads), pasta, and pizza.

The Alveograph continues to evolve today through new protocols (e.g., with adapted hydration) and completely open testing conditions (speed, time, and temperature), allowing it to adapt to modern challenges.

Constantly evolving in line with its designer, the Alveograph today is recognized both for quality control and as the go-to instrument for developing new products.

Tiếng Việt

Tiếng Việt